The Rohingya ‘Crisis’: U.S. Legacy and Current Policy in Southeast Asia

It’s all too easy for Western governments, their media and ‘NGOs’ to jerk the emotional chains of Western populations. A humanitarian crisis can be ongoing for years, but if Western governments have nothing to gain from it (or are partly responsible for it), the Western media says little about it and the populations of Western nations remain oblivious. If, on the other hand, Western governments decide that some beleaguered group of people should become the next humanitarian cause célèbre in service to some geopolitical intrigue, the Western press is activated and suddenly everyone is ‘up in arms’ with calls to ‘do something’ to help the poor [insert name of ethnic or religious group in specific geopolitical hotspot]. You could call it ‘humanitarian imperialism’.

The whole world has had several masterclasses in this kind of manipulation, from babies in incubators in Kuwait in 1991 to helping the poor Bosnian and Kosovar Muslims in Yugoslavia in 1999 to ’45 minutes to Iraqi WMD destruction’ in 2003, to the more recent and unsophisticated ploy of claiming that a given leader of a given nation is a ‘dictator killing his own people’. Despite these opportunities to inform themselves about how the world really works, like Pavlov’s dogs, the global population can still be relied on to react in the wrong way at the sounding of the ‘humanitarian’ bell.

Such is the case with the recent ‘humanitarian’ crisis in Myanmar where we’re told that the ‘Rohingya people’ are being persecuted by the Myanmar military, and in response a ‘formerly unknown group’, the ‘Rohingya Salvation Army’, began attacking Myanmar military posts on the border with Bangladesh in October 2016, killing policemen and provoking reprisals from Myanmar security forces that have continued this year, provoking the ‘humanitarian’ crisis that everyone in the West should be angry about. The source of the modern version of the crisis can be traced back to 2012 when riots broke out in Rakhine State when a Rakhine Buddhist woman was allegedly raped and murdered by Rohingya. Ten Rohingya were killed by Rakhine Buddhists in reprisal attacks. By August that year 57 Muslims and 31 Buddhists had been killed and an estimated 90,000 people were displaced by the violence. About 2,528 houses were also burned, 1,336 belonging to Rohingya Muslims and 1,192 to Rakhine Buddhists

While the Western media seems determined to present the situation in Rakhine State in the simplistic terms of a stateless people persecuted by the Myanmar authorities, the problem can only be understood in the context of the past and current geopolitical games that are being played by major world powers, most notably the USA.

Burma, East Pakistan and the ‘Great Game’

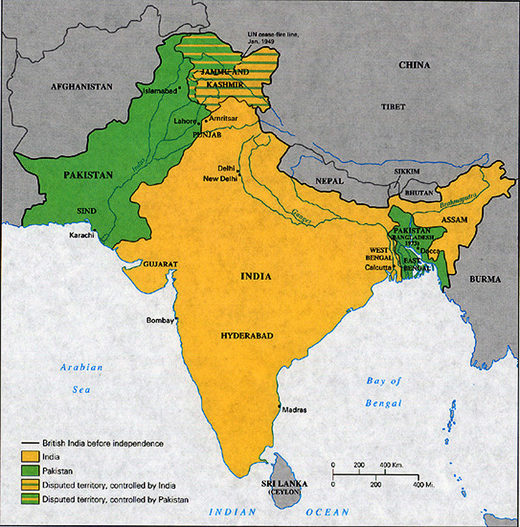

About 90% of the population of Myanmar are ‘East Asian’, that is, they look ‘oriental’, and the same number are Buddhist. In the Western Mayanmar state of Rakhine that borders the Bay of Bengal, there are about 5 million ethnic Rakhine or Arkanese people who are also mostly Buddhist and originally from the area that now encompasses Bangladesh and India. In addition there are about 1 million so-called ‘Rohingya people’ in Rahkine state who are Muslims and originally from Bangladesh, Pakistan and India. Many of the ‘Rohingya’ currently in Western Myanmar emigrated there over the course of the last century fleeing poverty and conflict in Bangladesh. During British rule in India, British authorities moved large numbers of people from Bengal (modern day Bangladesh) to British Burma to work on tea and rubber plantations. Thousands of Bengalis were also recruited by the Pakistani ISI (in league with the CIA) to fight the Soviets in Afghanistan.

Immediately after the Second World War the Bengali mujahideen from what was then East Pakistan called themselves ‘Rohingya’ and waged a low-level conflict with the Burmese authorities in an effort to ‘liberate’ North Rakhine state and incorporate it into what was then East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). When Burma gained independence (from the British) in 1948, the Burmese government accused the mujahideen (and by implication the Pakistani government) of encouraging the illegal immigration of thousands of Bengalis from East Pakistan into Rakhine state in an effort to annex it. Over the course of the next 10 years the Burmese military successfully defeated the ‘Rohingya’, i.e. Bengali mujahideen, forcing many to flee back to East Pakistan, although many Burmese Buddhists were killed. In 1962, as a result of minority groups, including the Bengali mujahideen, pushing for federalization of Myanmar, the Myanmar military took power in a coup that installed a dictatorship that lasted until 2011.

When British rule in India ended in the aftermath of the Second World War, the subcontinent was partitioned into India and Pakistan, with Pakistan as a Muslim majority state divided between two territories on each side of India. While the population of both areas was close to equal, West Pakistan had a much larger land mass and political power was concentrated there. In 1948 the government of Pakistan made Urdu the sole language of the new nation, provoking mass protests in Pakistan’s eastern territory (then called East Bengal) where the vast majority of people were Bengalese and spoke Bengali.

In 1949 Bengali nationalists formed the ‘All Pakistan Awami Muslim League’ to represent the interests of East Pakistanis. Facing rising sectarian tensions and mass discontent over the new law, the government outlawed public meetings and rallies. The students of the University of Dhaka and other political activists defied the law and organized a protest on 21 February 1952 that resulted in police killing several student demonstrators. The deaths provoked widespread civil unrest and after four years of further unrest, the central government relented and granted official status to the Bengali language in 1956. Despite this, the population of East Bengal (by 1955 it had been renamed East Pakistan) felt that they were being exploited by West Pakistan authorities and discriminated against in government, industry, bureaucracy and the armed forces. In 1953 the word ‘Muslim’ was dropped from the name of the Awami League to reflect the generally secular focus of the political group.

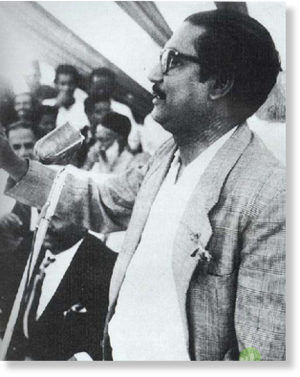

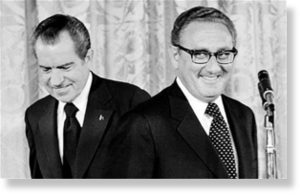

In 1970, when the Awami league under the leadership of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (known as the founding father of Bangladesh) won a landslide victory in the first open elections in a decade, the result was annulled by the military junta in West Pakistan and the Awami league launched the Six Point Movement (that called for greater autonomy for East Pakistan) and Non-Cooperation Movement that culminated in the Bangladesh Liberation War that involved the third military confrontation between Pakistan and India (the first two concerned Kashmir).The war was basically an attempt by the West Pakistan military government to crush the independence movement in East Pakistan, but given that these events were taking place at the height of the Cold War, the Pakistani government was certainly not acting alone. Pakistan was very much in the ‘Western’ (American) sphere of influence (since 1950) while India was ‘non-aligned’, which for Nixon’s National Security Adviser at the time, Henry Kissinger, meant ‘too friendly with the Soviets’.

Using weapons supplied to them by the Nixon government via Jordan and Iran (in violation of Congressional restrictions), the Western Pakistani military slaughtered at least 500,000 Bengalis. In this endeavor they were supported by Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami, an Islamist political party that advocated an extreme form of Islam and was strongly opposed to an independent Bangladesh. Activists of the party were known to be working with Pakistani intelligence (ISI) and therefore American intelligence operatives also. As a result of the genocide during the war, up to 2 million Bengali refugees fled to Rakhine state in Myanmar. Today, many of the Rohingya are these refugees and their children.

Unlike today, when U.S. governments tend to make a big deal of a dictatorship allegedly ‘killing their own people’, Nixon and Kissinger were unfazed by the very real genocidal tendencies of the West Pakistan government towards their subjects in East Pakistan.

As revealed by White House tapes and documents, Nixon and Kissinger were fully supportive of their Pakistani allies and angry that the Indian government was attempting to stop the madness. While discussing the matter in the Oval Office, Nixon told Kissinger that “the Indians need a mass famine” while Kissinger sneered at those people who “bleed for the dying Bengalis” and called India a “Soviet stooge”. The fact that Pakistan was the military dictatorship while India was the full-fledged democracy was irrelevant to these two paragons of virtue.

With the slaughter of East Pakistani Hindus and Bengalis well underway, a protest cable to Washington denouncing the U.S. government’s complicity in it was sent from the U.S. consulate in East Pakistan. It was signed by the Consul General, Archer Blood, and 20 members of staff. It stated, in part:

Our government has failed to denounce the suppression of democracy. Our government has failed to denounce atrocities. Our government has failed to take forceful measures to protect its citizens while at the same time bending over backwards to placate the West Pak[istan] dominated government and to lessen any deservedly negative international public relations impact against them.

Our government has evidenced what many will consider moral bankrupt, ironically at a time when the USSR sent President Yahya Khan [then President of Pakistan] a message defending democracy, condemning the arrest of a leader of a democratically-elected majority party, incidentally pro-West, and calling for an end to repressive measures and bloodshed….

But we have chosen not to intervene, even morally, on the grounds that the Awami conflict, in which unfortunately the overworked term genocide is applicable, is purely an internal matter of a sovereign state. Private Americans have expressed disgust. We, as professional civil servants, express our dissent with current policy and fervently hope that our true and lasting interests here can be defined and our policies redirected.

Consul General Archer Blood himself supplied an account of one episode of the genocide directly to the State Department and to Henry Kissinger’s National Security Council. He told how, having readied their ambush, Pakistani regular soldiers set fire to the women’s dormitory at the University in Dhaka; as the occupants fled the building they were mowed down with US-supplied machine guns. 10,000 people were killed in the first three days. Bengali intellectuals were also targeted (as is often the case in such situations) with up to 300 physicians, professors, writers and teachers rounded up and murdered during the last days of the conflict.

Nixon and Kissinger cannot, however, be accused of doing nothing at all in response to the situation. Soon after Archer Blood’s cable was sent, he was removed from his post and as soon as Kissinger became Secretary of State in 1973, he downgraded those who had signed the genocide protest in 1971.

In December 1971, the Pakistani army surrendered to the joint force of the Bengali ‘Mukti Bahini’ and Indian Army and the Bangladesh liberation war came to an end. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (the pro-West Awami League leader mentioned in Blood’s cable) was released from prison in West Pakistan and became the first Prime Minister of the new nation of Bangladesh. Apart from his dislike for the idea of independence for East Pakistan for geopolitical and ideological reasons, Kissinger had been burned by the bad press he had received over the war and he blamed the Awami League and its leader ‘Mujib’ (as Rahman was known). Soon he would have his revenge.

Transgenerational CIA Coups and America’s Jihad

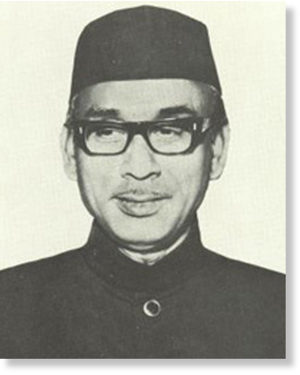

Mujib served as the first President of Bangladesh from 11 April 1971 to 12 January 1972 then as Prime Minister from 12 January 1972 to 24 January 1975 and then President again from 25 January 1975 to 15 August 1975. On the night of 15 August 1975, a group of junior army officers invaded the presidential residence with tanks and killed Mujib, his family and personal staff. Only his daughters Sheikh Hasina Wajed and Sheikh Rehana, who were visiting West Germany, escaped. As revealed by veteran US journalist Lawrence Lifschultz in a 2005 article in the Bangladeshi newspaper The Daily Star, the CIA had a direct hand in the assassination of Mujib that plunged Bangladesh into several years of bloody coups and counter-coups. Chief among the conspirators were Khondaker Mostaq Ahmad and General Ziaur Rahman. Mostaq was a member of the Awami League and a close confidant of Mujib’s. He had, however, also been secretly negotiating with U.S. officials and the Pakistani authorities in order to negotiate a settlement short of independence for Bangladesh.

A few months prior to the murder of Mujib and his family, Mostaq had approached the U.S. embassy to gain local U.S. support for the coup against Mujib. The U.S. ambassador in Dhaka at the time was Eugene Boster. Boster told Lawrence Lifschultz that in January 1975 he personally had given strict instructions that no Embassy personnel were to have further contact with any group contemplating a coup d’etat. This extended to the CIA Station Chief, Philip Cherry, and his staff. Boster believed however that an “end run” had been carried out circumventing his authority as ambassador. When Boster contemplated who in the U.S. State Deptartment could have had the authority or inclination to countermand the orders of the ambassador in Dhaka, the obvious answer was the ‘President of Foreign Policy’, Henry Kissinger, who was Secretary of State under the new Ford administration. When Lifschultz met with Mostaq in his home in Dhaka in 1976, months after the murder of Mujib and shortly after Mostaq himself had been deposed by General Ziaur Rahman, Mostaq refused to answer any questions about the coup, stating only that Lifschultz should ask Nixon and Kissinger since they “knew everything”.

Another conspirator in the U.S.-backed coup and murder of Mujib as revealed by Lifschultz was Ijlal Haider Zaidi, a high-level civil servant in the Pakistani government. In 1975, Zaidi was also a member of the ‘Afghan Cell’, a sort of clearing house for Pakistani intelligence and policy making in Afghanistan. This ‘Afghan cell’ was heavily infiltrated by U.S. and British intelligence and was responsible for assembling the seven religious Islamic parties of Afghanistan that Pakistan recognized as ‘legitimate rulers’. Within a few years these ‘legitimate rulers’ became the ‘Afghan mujihideen’ that were trained and armed by the CIA under ‘Operation Cyclone‘ (and publicly endorsed by U.S. National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski) to wage a war against the Soviets in Afghanistan. It’s no secret that the CIA and Brzezinski’s Afghan mujihideen would later transform into ‘al-Qaeda’.

In 2004 an assassination attempt was made on the daughter of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (‘Mujib’), Sheikh Hasina, who was the president of the opposition Awami League at the time. The attack was carried out by the Islamic fundamentalist organization, Harkat-ul-Jihad al-Islami, and involved members throwing 13 grenades into the crowd where Hasina was speaking. Also implicated in the attack was the aforementioned Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami, that had participated in the massacring of Bengalis in the 1971 Bangladesh liberation war and who were being financed by Pakistani intelligence and the CIA.

Hasina was injured but survived the attack and today is the Prime Minister of Bangladesh. In 2012, Tarique Rahman was tried in absentia for his involvement in the attack. Rahman is the current Senior Vice Chairman of Bangladesh Nationalist Party and the son of General Ziaur Rahman, who was involved in the coup and murder of Hasina’s father Mujib in 1975, after which he was installed as Chief of the Bangladeshi Armed Forces and was President from 1977-81, as outlined above.

In recent years, the Islamist groups implicated in the attack on Hasina (among many others) – Harkat-ul-Jihad al-Islami – is closely tied to ‘al-Qaeda’ and was led by Ilyas Kashmiri and Mufti Abdul Hannan. Both men were, unsurprisingly, trained by CIA and Pakistani forces in Afghanistan during the Soviet-Afghan war. Kashmiri, at least, went on to become a senior al-Qaeda figure and was involved in the 2008 Mumbai attacks and the assassination of Benazir Bhutto, to name but a few (a CIA asset is alleged to have provided logistics for the Mumbai attacks).

Harkat-ul-Jihad al-Islami is led by Abdul Quddus, a Burmese Muslim who fled to Pakistan sometime in the early 1980s. There he was recruited by the CIA and Pakistani ISI to wage war in Afghanistan. In 1988 the Burmese wing of the organization – Harakat-ul-Jihad-al-Islami Arakan – was formed with the goal of ‘liberating’ the Burmese state of Rakhine, which had a Muslim majority in the north. This group has recently surfaced in Myanmar and is leading the propaganda and military offensive to ‘free the Rohingya people’. The leader of the organization, Abdul Quddus, has well-documented links to Lashkar-e-Taiba, or the Army of the Righteous, one of South Asia’s largest Islamic terrorist organizations that operates mainly from Pakistan and is directly financed and armed by Pakistani intelligence, which itself is a puppet of the U.S. ‘deep state’. Lashkar-e-Taiba is known to be training recruits from Aceh, northern Sumatra, in preparation for jihad against Myanmar authorities in Rakhine State. The other group implicated in the assassination attack on Hasina – Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami – has also appeared on the scene in support of the ‘Rohingya’ and their (alleged) claim to an independent homeland in Myanmar.

Concerning the attacks by unknown ‘insurgents’ on August 25th this year on more than 20 Myanmar military posts in Rakhine State, it is now clear that the simultaneous attacks required meticulous planning. In the months before the attacks, as many as 50 people, Muslims as well as Buddhists suspected of serving as government informants, had their throats slit or were hacked to death in order to deprive the Myanmar military of intelligence in the area. Recent reports from journalists working the area of Northern Rakhine State strongly suggest that local people, Bengali Muslims and Buddhists alike, are furious that these ‘jihadis’ have provoked Myanmar authorities into attacking villages in the area.

Sowing Discord In Southeast Asia: Target China

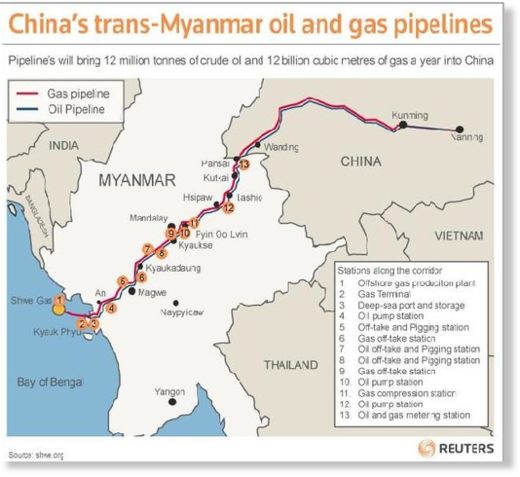

Off the coast of Rakhine State, there’s a huge gas field called ‘Than Shwe’, named after the general who last ruled Myanmar. The massive energy reserve was discovered in 2004. By 2012, when the first riots and refugee crisis began in Rakhine state, China had almost completed the development of one part of the gas field. Today China has connected Myanmar’s port of Kyaukphyu (in Rakhine State) with the Chinese city of Kunming in Yunnan province via one oil and one natural gas pipeline. The oil pipeline delivers Middle Eastern and African crude, while the gas pipeline transports hydrocarbons from the Than Shwe field, to China. These pipelines are strategically important for China not only to diversify its energy supplies but also as an alternative to using the Malacca Straits shipping route through which 80 percent of all Chinese sea-borne imports and exports pass. In 2015, in a not so subtle message to China, the U.S., Japanese, Australian and Singaporean navies participated in the ‘Talisman Sabre’ naval exercises that simulated the blockading of the straits.

Under cover of a genuine humanitarian crisis, conflict in north Rakhine state can potentially spread south and to other parts of Myanmar, threatening the existing Chinese pipelines there. China also has several future planned Chinese projects in the country, including the $10 billion Kyauk Pyu Special Economic Zone operated by China’s state-run CITIC Group that China claims will create 100,000 jobs in one of Myanmar’s poorest regions. By creating a pocket of instability on China’s doorstep in Myanmar, Beijing’s ‘Belt and Road’ initiative – which aims to economically unite Eurasia – is also put at risk. If jihadist groups can gain a foothold in Myanmar, several other South Asia nations may become infected. In addition, by demonizing the Myanmar authorities for persecution of ‘Rohingya’ Muslims, a wedge may be driven between the Myanmar government and other Muslim-majority Asian nations like Indonesia and Malaysia.

All of these tactics appear to form a part of the U.S. government’s “pivot” to Asia that was officially unveiled by the Obama administration in 2011. From an overt military perspective, this ‘pivot’ aims to concentrate 60 percent of the U.S. Navy and Air Force in the SE Asia region. From a covert military and political perspective, it involves developing a network of military alliances and partnerships – including covert U.S. support for jihadist mercenaries (as they have done in Syria) – that are necessary to wage war against China.

So what’s the take home message? The ‘Rohingya people’ are ethnic Bengalis from Bangladesh. They do not ‘belong’ in Myanmar. The reason they are there is due to several factors, all of them the result of Western meddling in, and mismanagement of, South East Asia over the past 100 years. Today, the plight of these people is being exploited by jihadist groups that have historically been used as tools of Western intelligence agencies as they continue to play their centuries-old ‘great game’ of world domination.

As with so many other humanitarian crises, there is no real concern among Western politicians or their media for the plight of the Bengali immigrants in Myanmar. The bottom line seems to be that the ‘Rohingya’ are relatively recent arrivals from Bangladesh. They are illegal immigrants that the Myanmar government has been struggling to cope with for several decades because they have been the source of periodic and serious conflicts with the local Buddhist population in West Myanmar who fear that, as more and more Bangladeshi immigrants come in, the local Buddhist culture and religion will be wiped out. On top of that fairly normal crisis (these days anyway), there are jihadis exploiting it and rabble rousing on behalf of Pakistani ISI and their Western buddies, in service to grander geopolitical agendas i.e. ‘get China’. Or so it all seems.

As Kissinger himself said (echoing the words of the British Lord Palmerston, another fan of genocide): “America has no permanent friends or enemies, only interests.” America is no friend of the Bengali immigrants in Myanmar, or any other oppressed and disenfranchised group of people anywhere in the world. Rather, they are seen as opportunities to be exploited in the Western psychopathic elite’s perpetual drive for power and control over as much of the world’s natural and human resources as possible.